What’s going on elsewhere in Cambridgeshire, the Gardens Trust or neighbouring county Trusts

If you know of an event or activity that you think may be of interest, please contact admin@cambridgeshiregardenstrust.org.uk

Young Horticulturalist of the Year

The Chartered Institute of Horticulture is pleased to announce that the Young Horticulturist of the Year Competition 2026 will open for entries on Sunday, 1 February 2026.

The competition is open to anyone across the UK and Ireland who is under 30 on 31 July 2026. It offers entrants the opportunity to test their horticultural knowledge, broaden their experience, and connect with others across the sector.

This long-established competition provides a unique platform for emerging horticulturists to showcase their skills. The overall winner will receive the prestigious title of Young Horticulturist of the Year along with a £2,500 travel bursary from The Percy Thrower Trust, generously provided by the Shropshire Horticultural Society. The bursary supports a horticultural study trip anywhere in the world, enabling the winner to explore new ideas, research, or practical experience within their chosen field.

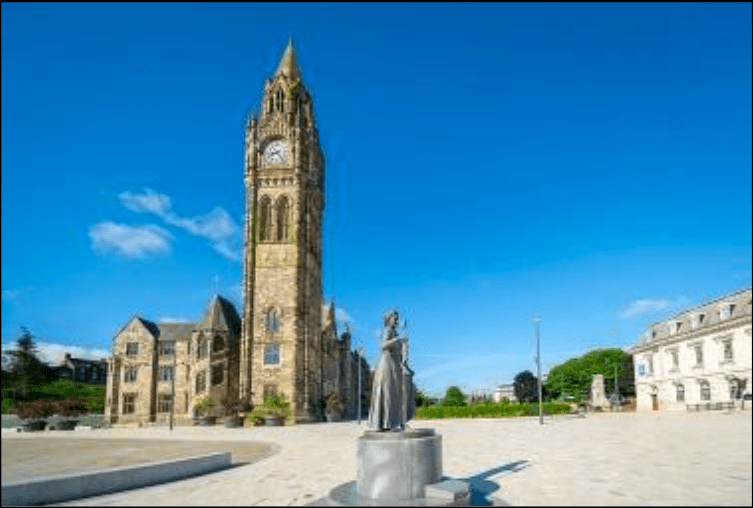

The Grand Final will take place on Saturday, 16 May 2026, in the Bright Hall at Rochdale Town Hall (see photos below). Further details about the competition and how to take part can be found here

IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT:

Review of Gardens Trust role in Planning

and Appeal to Support a Fighting Fund

The government is considering removing the Gardens Trust as a Statutory Consultee in the English planning system. The Gardens Trust has published a statement about this which can be viewed on their website here: The Gardens Trust’s response to the government’s intention to consult on removing it as a statutory consultee – The Gardens Trust.

The consultation period closed on 13 January 2026 and on 14 January 2026, the Gardens Trust issued this updated press release.

The Gardens Trust has now launched an appeal to all county gardens trusts members to contribute to a Fighting Fund to challenge the proposals. For further information and to contribute, please follow this link.

Resources and forthcoming events

Run the London Marathon with Team Gardens Trust

Flushed with success from Linden Groves’ completion of the London Marathon this year, the Gardens Trust has purchased nine charity places in the 2026 London Marathon, and they are inviting runners to join the Gardens Trust team. Whether you are a seasoned marathoner or a first-timer, you can experience the thrill of the race while supporting the conservation of gardens and landscapes across the UK.

Key details

- A unique chance to run in one of the world’s most prestigious marathons

- Training and fundraising support provided

- Minimum fundraising commitment: £2,500

The 2026 London Marathon takes place on Sunday 26 April. For further information on participation and how to apply, please visit the GT Marathon webpage.

Free training from The Gardens Trust in research and recording

As part of the Nottinghamshire’s Garden Story project, The Gardens Trust is offering free training events, open to all, beginning later on this month and running into 2024. Most are online and anyone is free to attend, whether you are taking part in the project or not.

The project is aimed at recruiting and training new volunteers in research and recording and includes the following sessions (see this pdf for full details on sessions and dates):

* An Introduction to Garden History

* Understanding the threats facing historic parks and gardens

* Beginning Historic Designed Landscape research

* Recording Landscapes (in-person session)

* Collecting memories and how to share your research

These sessions may be of interest to new volunteers or anyone thinking about running a similar project. The Gardens Trust will be opening up bookings for the sessions during the week of 6th November, via their events page.

Other resources from the project, such as slides and handouts, will be available at The Gardens Trust online Resource Hub.

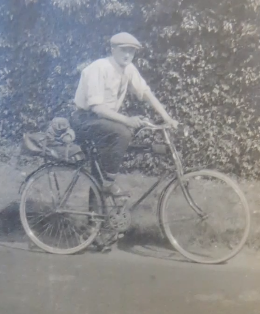

Photo RHS Libraries Archive

The Bicycle Boys

Loyal Johnson (1905-1999), an American horticultural student, visited Britain in 1928 with his friend Sam Brewster. Together they undertook a three-month tour of English, Welsh and Scottish gardens, covering 1500 miles on bicycles (see above). In total the young men visited around 70 gardens, including Munstead Wood where Gertrude Jekyll was in residence, Gravetye Manor with garden paths adapted for William Robinson’s wheelchair, Great Dixter where they were reprimanded by Nathaniel Lloyd before getting a guided tour, Aldenham House, Chatsworth, Levens Hall, Blickling, Hestercombe House, Hoar Cross House, Compton Wynyates, Blenheim Palace, the Sutton Nursery Company at Reading and many others, including a visit to Emmanuel College in late August 1928. Loyal kept a detailed diary of the trip in three volumes, describing the gardens they visited, the places they stayed and the people they met, creating a historical and social record of inter-war Britain and its gardens.

Johnson’s diaries and photograph albums were donated by his son Marshall to the RHS Lindley Library in 2015 and feature in an exciting new online exhibition The Bicycle Boys: An Unforgettable Garden Tour, launched on 8 June 2022 on the RHS Libraries Digital Collections. The exhibition forms part of the Gardens Trust’s Unforgettable Gardens campaign to raise awareness of the value of local parks and gardens and the importance of protecting them for our future.

Gin Warren of CGT has worked with Amanda Goode, the Emmanuel College Archivist, to research Johnson’s visit to Cambridge and to the college. Arriving in Liverpool from the RMS Laconia on 18 June 1928, Loyal and Sam bought bicycles and suitcases for their equipment and set off on their tour. By the time they arrived in Cambridge on 29 August, they had cycled through the north, the midlands, the west country, much of southern England, including London, and were heading north again. They had seen many towns and cities and yet Sam noted I think I like Cambridge the best of any place I have seen yet. It can be compared to Oxford yet it is so different. Being the long vacation, Cambridge would have been quiet and Sam could engage with a number of college gardeners. At Emmanuel College he observed that it has large gardens and a swan pool and a nice outdoor swimming pool too. However, his brief comment on Emmanuel’s water features covers a multitude of connections, some less savoury than others…

Emmanuel College ponds

As keen readers of Liz Whittle’s articles in Garden History or the CGT Newsletter will be aware, Emmanuel College is fed by water from Hobson’s Conduit. This is the same Thomas Hobson (1544-1631) who made his fortune in carriage between London and Cambridge and is said to have given customers of his livery stables the eponymous choice as to which horse they could select. With others, Hobson helped fund construction of the conduit and left a legacy for its maintenance which is managed by the Hobson’s Conduit Trust: Liz Whittle, CGT chairman, is also vice-chairman of the Conduit Trust.

In 1610 water rising in the Ninewells Springs near Great Shelford was diverted from the Vicar’s Brook into a new course, called Hobson’s River or Brook, running alongside Trumpington Road and the Botanic Gardens and ending up at the present-day Conduit Head at Lensfield Road (see figure above). Originally intended to flush the pestilential King’s Ditch and improve sanitation, the supply quickly became an important source of drinking water. Several water runs were built from Conduit Head and, in 1631, a branch was constructed along present-day Lensfield Road and St Andrew’s Street towards Drummer Street where it splits into feeds that ran into Emmanuel and Christ’s Colleges, as well as a public dipping point. The colleges wanted the water for their ornamental pools which still survive in altered form. Emmanuel College took the water via Chapman’s Garden to feed a large pond – originally a mediaeval fishpond for the college’s founding Dominican monks – that is shown in Loggan’s 1690 Cantabrigia Illustrata and, in the 19C, a rectangular pond in the Fellows’ Garden, the swimming pool noted by Loyal Johnson in 1928. Today, the conduit water supplies the curved pond in Chapman’s Garden, the more informally landscaped main Paddock pond and, after appropriate filtration, the Fellows’ Garden swimming pool (see below).

‘Swan Pool’ and the Anatomists

In the Long Vacation of 1928, there weren’t many people around to tell the Bicycle Boys the history and stories connected with Emmanuel’s gardens. Loyal had noted the ‘Swan Pool’ (now the main pond in The Paddock), but apparently nobody told him that it had been the hiding place for a stolen corpse.

Stolen corpse? Not in Rembrandt’s 1632 painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp that followed the dissection of Aris Kindt, aka Adriaan Adriaanszoon, who was hanged for armed robbery. Rembrandt painted the scene on the day he was executed. In Amsterdam, one dissection of an executed criminal a year was allowed, so this was not a stolen corpse.

A little earlier, William Harvey, Fellow of Gonville and Caius College and physician to King James I, was teaching anatomy in London, having studied in Padua under Italian anatomist and surgeon, Hieronymous Fabricius. Using both mathematics and empirical science, including dissections of executed criminals, Harvey demonstrated that Galen’s assertion, that the liver made blood which then flowed to the extremities, could not possibly be correct. Harvey published De Motu Cordis in 1628 and medical science was never the same again: unquestioning reliance on classical sources and belief systems was demolished, and purposeful experimentation became part of the scientific method.

Stolen corpse in Cambridge in the 1730s? Yes: two Fellows of Emmanuel College dug up the body of someone newly buried in Fen Ditton – or made arrangements for it to be exhumed for them. The deceased’s friends and relatives realised what had happened and stormed the college. They searched diligently but failed to find the body, as it had been wrapped and weighted down in the Swan Pool for later recovery.

Body snatching was apparently rare in 18C Britain: the high execution rate, even for trivial crimes, assured supply. Furthermore, the 1751 Murder Act prevented the bodies of convicted murderers from being buried – they were either displayed publicly or handed over for dissection. By the early 19C the number of executions had fallen to around 55 a year, while the growth of surgical science meant that about 500 bodies were needed. Stealing bodies from churchyards probably wasn’t difficult because many in towns were so full that new burials were very shallow, in graves which had been pre-used many times. Christopher Wren and John Evelyn had noted how disgusting urban graveyards were in the 17C and, by the early 19C, churchyard overcrowding and the consequent opportunity for body-snatching were significant issues.

In London, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham had drawn attention to the problem and, in 1828, a parliamentary select committee had drafted a Bill for preventing the unlawful disinterment of human bodies, and for regulating Schools of Anatomy. The House of Lords threw it out in 1829. Bentham subsequently left his own body to be publicly dissected (1832), to try to change public opinion on the topic.

Families who could afford it tried to protect fresh graves. J.C. Loudon reported several methods of thwarting body-snatchers in his 1843 book On the laying out, planting, and managing of cemeteries and on the improvement of churchyards. These included building walls and fences, hiring watchmen, creating very deep graves, and even using a mortsafe – a weighty cast-iron box, toremain over the coffin for six of eight weeks, till decomposition rendered the body unfit for the purposes of the anatomist. The mortsafe was then disinterred for reuse and the grave completed in the usual manner.

The problem of locating the recently deceased could be circumvented by procuring their death. Burke and Hare infamously provided for the surgeons and anatomists of Edinburgh in 1827-8, probably murdering 16 people on their lucrative spree. Burke and Hare were paid £8 to £10 per body, whereas Burke’s day-job as a cobbler earned him around £1 a week.

The Anatomy Act of 1832, the year of Bentham’s dissection, finally enabled Anatomy Schools to collect from workhouses, prisons and hospitals bodies which had not been claimed for burial in the 48 hours after death. It was deeply resented by the poor, because prior to the Act they had run the same risk as everyone else of being body-snatched and dissected. Now it was systematically they who were dissected, like common criminals, and Loudon tells us that they felt this keenly. In fact, it was one of the reasons for the rejection of the 1828 bill, as the reformer William Cobbett opined, ‘They tell us it was necessary for science. Science? Why, who is science for? Not for poor people. Then if it is necessary for science, let them have the bodies of the rich, for whose benefit science is cultivated.’

Swim Swan Swim

It is somewhat ironic that two swans in Emmanuel’s Pond helped to overthrow a theory expounded by Cambridge’s greatest physicist, Sir Isaac Newton. Newton had studied optics throughout his life and had made huge achievements in understanding the nature of light based on careful experimentation. His great work, Opticks (1704), is one of the earliest approaches to scientific understanding based on applying mathematics to experiments, in contrast to applying deductive reasoning based on assumptions or axioms. In it, Newton maintained that light from a candle consisted of a stream of tiny particles, called corpuscles, that were emitted by the candle, travelled in straight lines and entered the eye to create the perception of light and colour. Newton’s corpuscular theory contrasted with the wave theory of light, proposed by Christiaan Huygens in 1678, and such was the overwhelming weight of Newton’s reputation that Huygens’ wave theory was consigned to the deep-freeze of history for 125 years.

Copyright © The Royal Society.

Enter Thomas Young (1773-1829); a polymath whom some considered to be the last man who knew everything. Young was the eldest of 10 children and was fluent in both Greek and Latin by the age of 14. He studied medicine at Bart’s Hospital, Edinburgh University and the University of Göttingen, and was elected to a Fellowship of the Royal Society at the age of 21 after writing a paper on visual accommodation in the eye. In 1797, Young entered Emmanuel College and, in 1799, set himself up as a physician in London. Despite launching a successful medical career, Young was appointed professor of natural philosophy (i.e. physics) in 1801 at the recently founded Royal Institution, where he delivered 91 lectures in the course of two years.

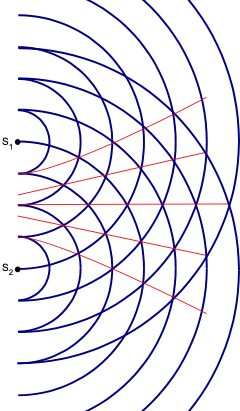

While at Cambridge, Young became interested in the nature of light and, in 1803, he conducted an experiment which eventually fired a cannonball through the corpuscular theory and holed it below the waterline. It is said that while observing the pattern of ripples created by two swans swimming in Emmanuel’s Pond, Young noticed that, in places, ripple-peaks from one swan coincided with troughs from the other swan and cancelled each other out. He created a ripple tank to demonstrate the effect on water waves under controlled conditions. (See schematic figure to the right. Red lines link points where the two sets of waves from ‘swans’ S1 and S2 reinforce each other; nulls occur mid-way between each red line where the waves cancel each other out.) He then extended his experiment to see whether similar patterns could be observed using light instead of water waves.

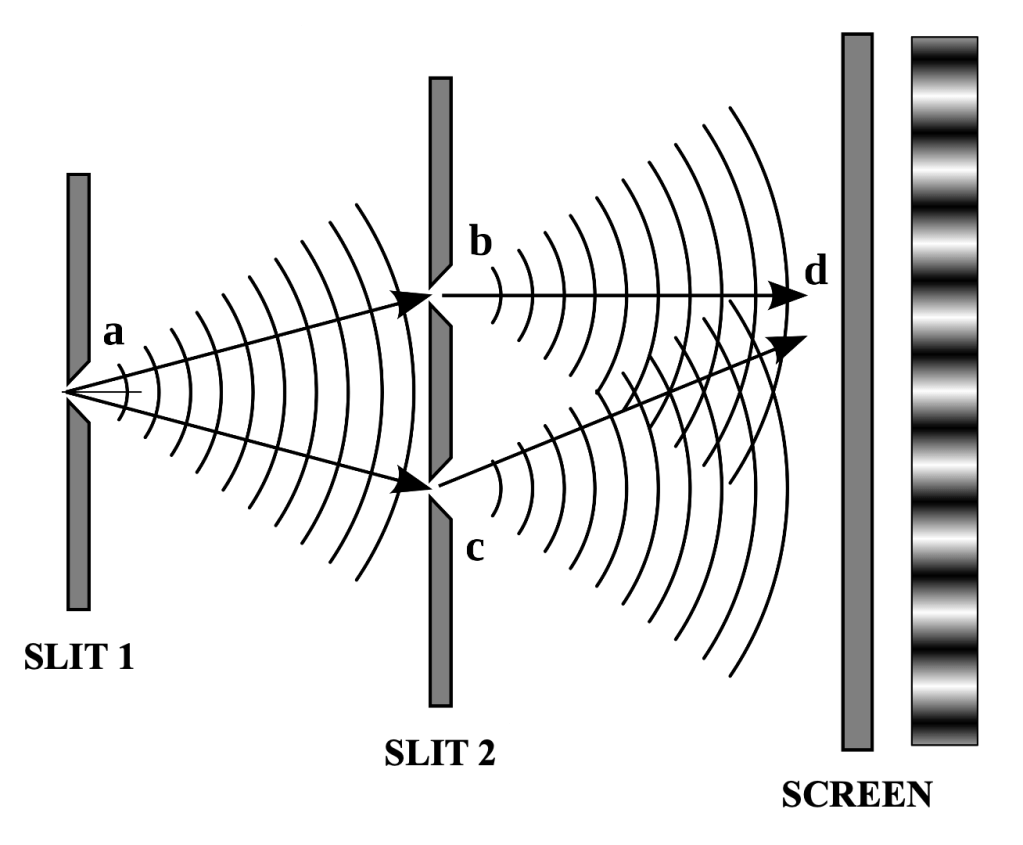

Young devised his eponymous two-slit interference experiment, whereby light from a single narrow primary slit (a in figure) illuminated two further slits (b and c), arranged at equal distance from the centre line. Each secondary slit acts as a source of light which falls on a screen (d) where Young observed a pattern of light and dark stripes, spreading symmetrically from a bright, central stripe. He inferred, correctly, that light from each secondary slit was interfering with light from the other slit and, because both slits were illuminated by light from the same primary slit, the stripes were due to constructive and destructive interference, just like the water ripples from the two swans.

Young’s famous experiment was the first physical proof of the wave nature of light and his experiments were supported by theory from others, such as Augustin-Jean Fresnel, to explain and quantify his observations. In the 20C, Albert Einstein gave some solace to corpusculists by demonstrating that light could interact with matter both as a wave and as a particle, a concept from quantum mechanics known as wave-particle duality, but modern physics recognises light as a part of the electromagnetic wave spectrum, beautifully described by James Clerk Maxwell in his eponymous equations. Young had an illustrious career, with major contributions to sound, optics, elasticity, a theory of tides and the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone. He advised on the introduction of gas lighting in London and was foreign secretary at the Royal Society. His monument in Westminster Abbey recognises his achievements as being from a ‘man alike eminent in almost every department of human learning’: an appropriate epitaph for a polymath.

The Gardens Trust offers a wide variety of talks and events. Please see their events webpage for full details. Information on Gardens Trust training courses that cover Conservation and Plannning can be found on our Planning Resources page.